LOYALTY PLATFORM

Customer loyalty made easy

Create a loyalty program tailored to your business with our intuitive, all-in-one platform

Brevo (formerly Sendinblue) is a top-rated marketing solution

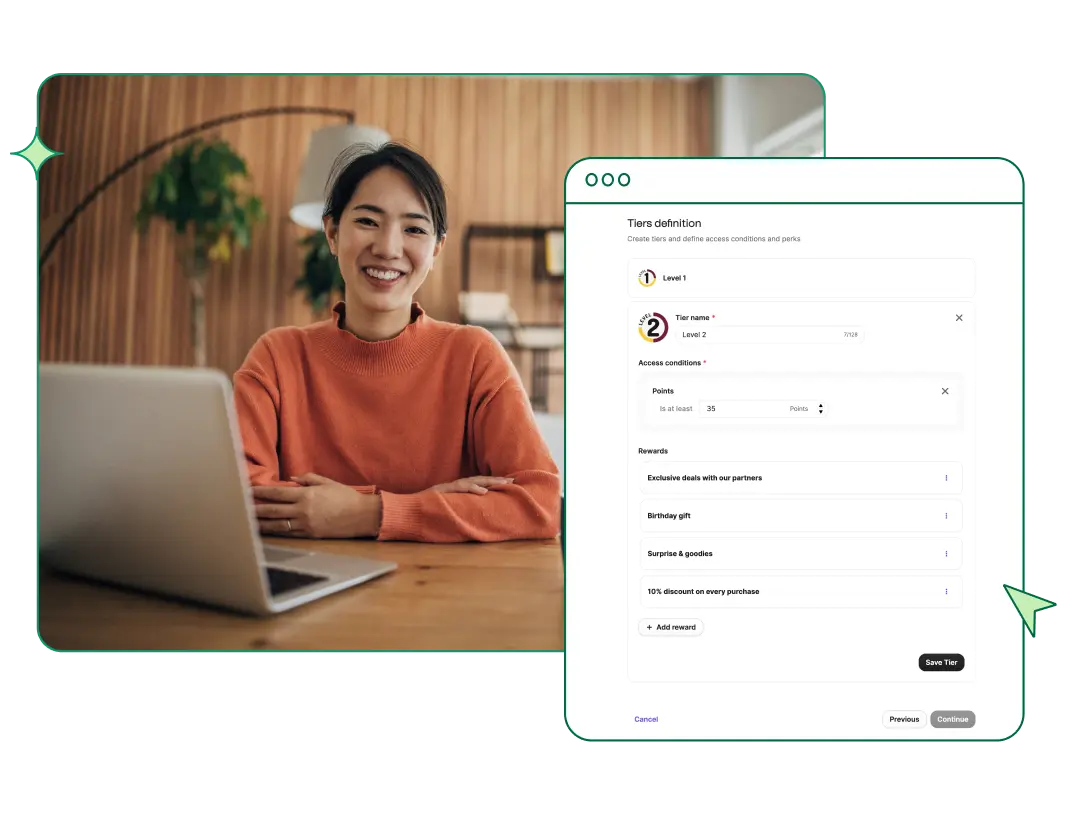

A dedicated team to help you design a loyalty program that perfectly matches your brand

Longer retention

Loyalty programs cause customers to remain customers longer through more meaningful engagement.Larger purchases

Companies with loyalty programs see increased purchase frequency and higher average cart value.Deeper insights

Knowing how your customers interact with you lets you adapt your communications their preferences.Understand customer needs and expectations

Analyze your customers’ buying habits to uncover what they value most, such as discounts, complimentary items, or unique experiences.Regularly collect customer feedback to adapt your program to meet their needs and expectations.

Offer flexible rewards

Provide a variety of rewards, such as discounts, free products, event invitations, or personalized services.Set attainable rewards to keep customers motivated and engaged without causing frustration.

Simplify enrollment and usage

Provide quick and easy registration, using options like a mobile app or digital card.Define clear and straightforward rules for earning and using loyalty points.

4.8x

Loyalty programs on average generate 4.8x more revenue than they cost.

10x

Retaining an existing customer costs you up to 10 times less than acquiring a new one

60%

Nearly 60% of customers who are members of a loyalty program spend more

Try Loyalty today

Book a call with our team to explore the Loyalty platformPersonalize your customer experience

Integrate tools like mobile wallets and CRM solutions to track customer behaviors and tailor offers to their preferences.Send push notifications and emails to notify your customers about special offers, upcoming events, and available rewards.

Maximize customer engagement

Award bonus points or rewards for specific activities, like regular visits, referrals, and event registrations.Offer special deals exclusively for loyalty program members, such as exclusive discounts or previews.

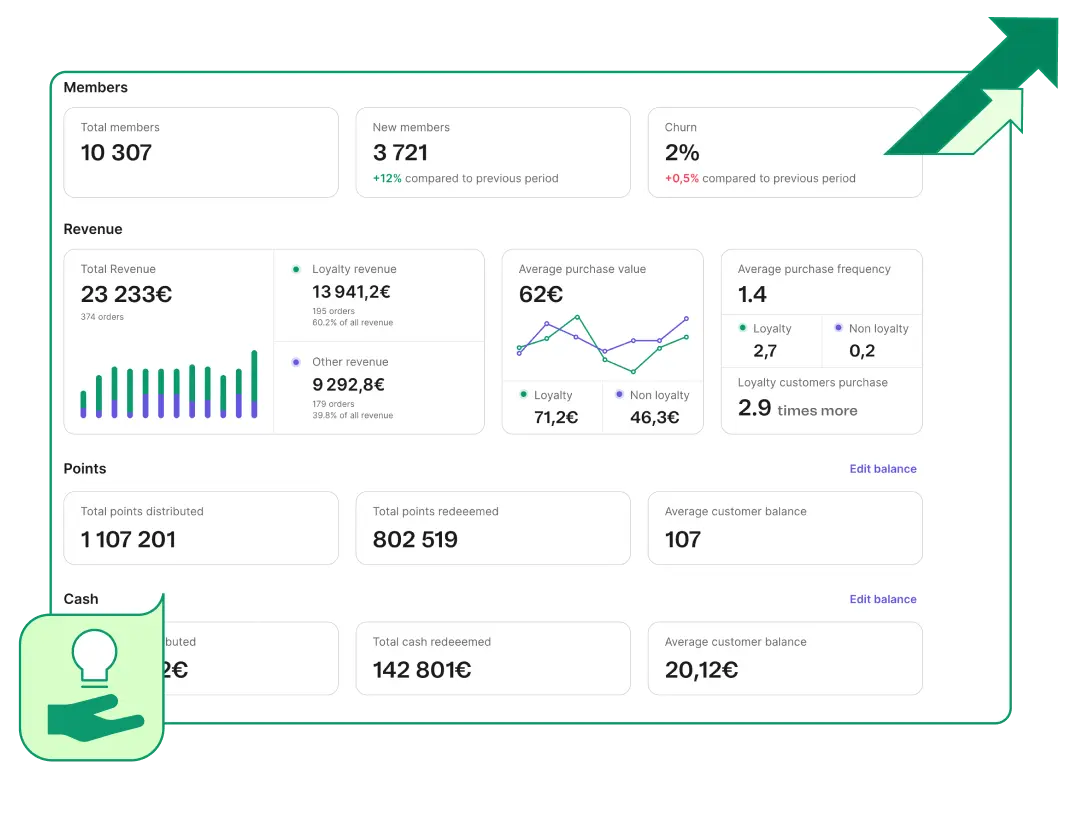

Measure and optimize program performance

Define and measure key performance indicators like member count, visit frequency, spending levels, and conversion rates.Analyze collected data to assess the program’s effectiveness and make adjustments to improve results.

Try Loyalty today

Book a call with our team to explore the Loyalty platformLearn more about Loyalty